BETTER TOUCH BETTER BUSINESS

Contact Sales at KAIDI.

In the field of industrial liquid level measurement, radar technology has reached a high level of maturity. Whether in petrochemicals, chemical processing, energy, or water treatment industries, radar level transmitters have become the de facto standard. Yet a persistent challenge remains in practical engineering projects: Why do some applications strongly favor guided wave radar while others insist on conventional radar level transmitters? Simply citing “contact/non-contact” as the reason often fails to justify the actual engineering decisions.

In fact, guided wave radar and radar level gauges are not simply interchangeable. They address two distinct types of uncertainty issues, based on different measurement assumptions, and thus each has its own validity and limitations.

The essence of liquid level measurement is not “measurement.”

In industrial settings, liquid levels are not ideal, stable, or clearly defined geometric interfaces.

Any liquid level measurement inherently involves navigating uncertainty, primarily manifested in three aspects:

1. Interface UncertaintyFoam, emulsification, turbulence, and blurred stratification render the “liquid surface” itself indistinct.

2. Uncertainty in transmission pathwaysSteam, dust, pressure fluctuations, and internal tank structures render signal propagation unpredictable.

3. Sensor Status UncertaintyCondensation, material buildup, crystallization, aging—altering the sensor's own “operating boundary conditions”

The fundamental difference between guided wave radar and radar level gauges lies not in which is more advanced, but in how they position uncertainty in entirely different ways.

Radar Level Transmitter

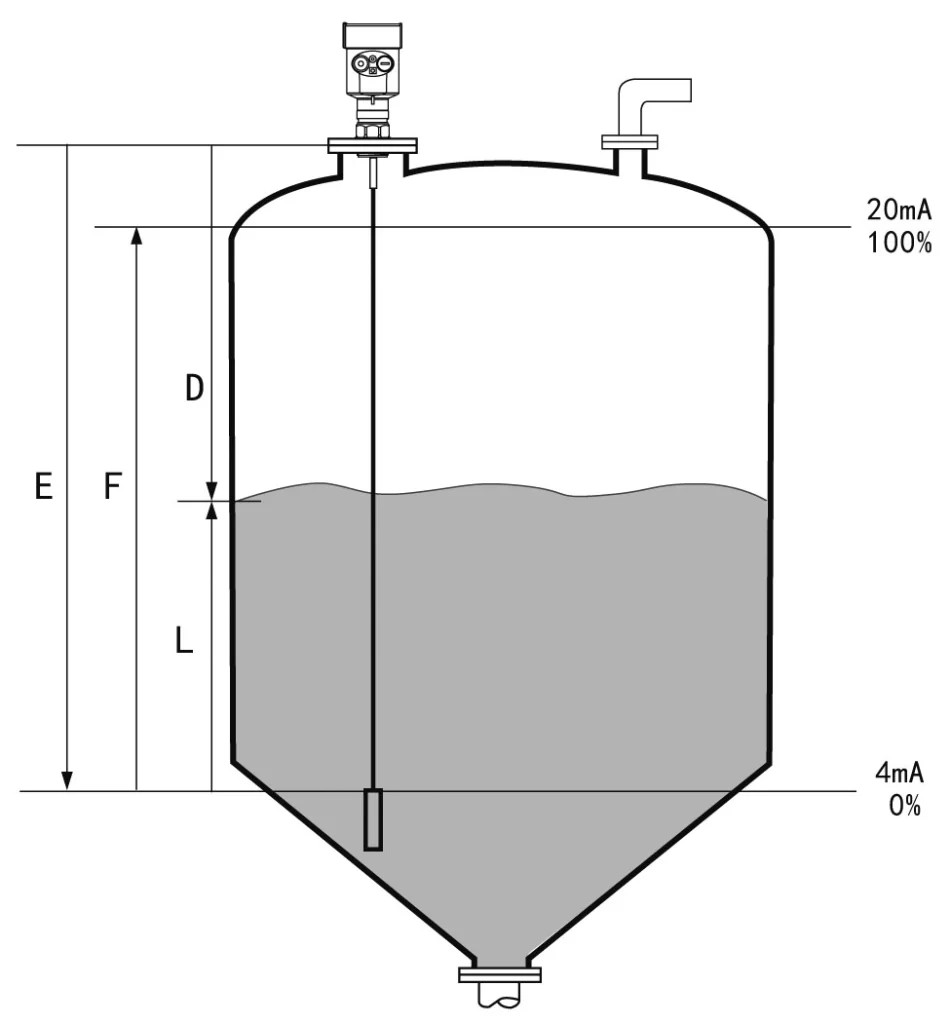

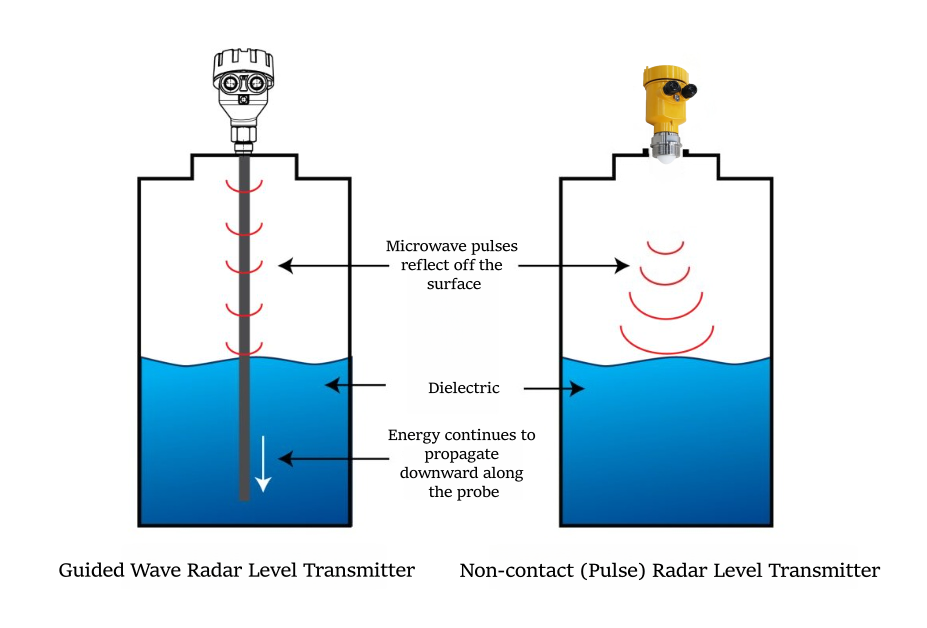

The radar level gauge transmits microwave signals downward via its antenna. Electromagnetic waves propagate through the vapor space inside the tank, reflect off the liquid surface, and return to calculate the liquid level.

Its technical advantages are clear:

• Fully non-contact, avoiding medium corrosion, adhesion, and contamination

• Suitable for high-temperature, high-pressure, highly corrosive, and sanitary conditions

• Capable of ultra-wide measurement ranges, ideal for large storage tanks and spherical tanks

• Eliminates mechanical risks like probe scaling or deformation during long-term operation

For these reasons, radar level gauges are virtually irreplaceable in applications such as crude oil storage tanks, refined oil tanks, and large vertical chemical tanks.

However, it is important to note that all these advantages are built upon an implicit premise:

The liquid level must be a “clearly identifiable target in space” in electromagnetic terms.

When this premise is compromised, the challenges faced by radar level gauges become immediately apparent:

• Steam density variations cause propagation attenuation and refraction

• Foam and dust introduce scattering and false echoes

• Internal components like agitators and coils create strong reflections

Violent liquid surface fluctuations causing unstable echoes

In such scenarios, radar level transmitters are not “unusable,” but their performance becomes highly dependent on algorithms, echo recognition strategies, and engineering expertise to accurately pinpoint the true liquid level amidst complex echoes.

Guided Wave Radar

Guided wave radar employs a different measurement logic.

Instead of allowing electromagnetic waves to propagate freely within the tank, it confines the signal to travel near the guide wave body via a probe rod or steel cable. This design fundamentally alters the distribution of measurement uncertainty:

• Fixed signal path significantly reduces spatial environmental impact

• Insensitive to vapor, foam, dust, and other gas-phase interferences

• Easier acquisition of identifiable echoes from low-dielectric-constant media

• Stable echo structure enhances repeatability and trend control

Consequently, guided wave radar often achieves more stable signal acquisition in challenging conditions characterized by complex spatial constraints, strong vapor interference, and weakly reflective media.

However, this stability comes at a cost. The advantages of guided wave radar are achieved through direct contact with the medium, which also defines its clear limitations:

• The probe may experience material buildup, crystallization, or polymerization

•High-viscosity media may coat the guided wave body, causing echo attenuation

•Strong mechanical vibrations or liquid level impacts can affect cable stability

•In ultra-long-range, large-diameter tanks, structural and installation constraints are significant

In other words, guided wave radar reduces “spatial uncertainty” but significantly increases the influence of sensor surface conditions on measurement results.

The dielectric constant is not a matter of “whether it can be measured.”

In engineering discussions, dielectric constant is often simplified to “whether it can be measured,” but in practical applications, it primarily affects measurement margin and stability.

• For radar level gauges, a low dielectric constant means weak reflections. When combined with spatial interferences like steam or foam, echoes are easily drowned out.

• For guided wave radar, low dielectric constants similarly weaken reflections. However, due to concentrated energy and high coupling efficiency, identifiable echoes are often maintained.

This does not imply guided wave radar is “immune to dielectric constant effects,” but rather that it transforms the challenge into: Can a stable impedance transition be formed along the guided path?

Interface Measurement

In processes such as oil-water separation, extraction, and sedimentation, interface measurement serves as a critical control parameter. Guided wave radar can generate multiple reflection points at both gas-liquid and liquid-liquid interfaces when the dielectric constant difference between the two phases is sufficiently large, enabling simultaneous measurement of liquid level and interface. This capability is fundamental to guided wave radar but is not inherently guaranteed; it depends on:

• Whether the dielectric constant difference between the two phases is sufficiently pronounced

• Whether the interface is clear and stable

• Whether the probe consistently remains within the interface transition zone

In cases of unstable interfaces, severe emulsification, or blurred stratification, radar or other measurement methods may prove more suitable.

Emphasis on anti-interference capability

A frequently overlooked yet critically important fact is that:

• Radar level gauges are primarily influenced by spatial conditions

• Guided wave radar is primarily affected by the surface condition of the sensor

This means the “interference resistance” of the two technologies cannot be simply compared.

In steam-filled reactors with complex internal structures and bubbling foam, radar level gauges face significantly increased difficulty in echo recognition;

Meanwhile, guided wave radar may become a long-term maintenance burden in media prone to crystallization, adhesion, or polymerization.

Conclusion

From an operational cycle perspective, each technology excels at addressing distinct challenges:

• In clean, large-scale, non-contact-intensive applications, radar level gauges demonstrate superior long-term reliability

• In complex spaces where signals are prone to interference and measurement stability is paramount, guided wave radar maintains controllability more effectively

The core of engineering selection has never been about “short-term measurability,” but whether long-term failure modes are acceptable.

When operating conditions meet assumptions, technological advantages become evident; when assumptions are disrupted, even the most “advanced” instruments face significant challenges.

Understanding this is more important than memorizing whether to choose guided waves or radar.

We are here to help you! If you close the chatbox, you will automatically receive a response from us via email. Please be sure to leave your contact details so that we can better assist